N1: Plato

Poetry, Knowledge, Politics

This is the latest entry in my series discussing the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. For the first issue, start here.

My dear Glaucon, we are engaged in a great struggle, a struggle greater than it seems. The issue is whether we shall become good or bad. And neither money, office, honor, nor poetry itself must be allowed to persuade us to neglect justice or any other virtue.

Plato, Republic, Book X

Plato

We begin a bit out of order; Gorgias of Leontini, whoever that is, predates Plato by a few decades and is presented first in the anthology, but much of Gorgias’s significance is the opposition he represents to Platonic thought, despite coming before him. So for now, let’s get a grip on the big dog himself.

Plato (ca. 427 -ca. 347 B.C.E.) was a philosopher in Athens, then an independent city-state not yet unified with the rest of what we now call Greece. He was not the first philosopher, in Athens or otherwise, but he is undoubtedly the most influential. Why? For one, he wrote a ton (Socrates apparently wrote nothing) and all of it survived. He also wrote broadly enough that his writings “engage almost every issue that interests philosophers: the nature of being; the question of how we come to know things; the proper ordering of human society; and the nature of justice, truth, the good, love, and beauty.”1

Plato did not write extensively on literature, but his few thoughts on the matter reveal serious admiration, skepticism, and even fear of language’s power to affect the mind and represent (or distort) capital T Truth, leading him to famously censor poetry from the ideal city in his most well-known work, Republic. From this dialogue also comes the Allegory of the Cave, which still remains one of the most startling uses of the literary device to this day.

There are two major events that lurk in the background of Plato’s writing: the Peloponnesian War and the execution of Socrates, Plato’s teacher and friend, by the Athenian state. The former, a devastating and ineptly managed conflict between Athens and Sparta, explains Plato’s preference for aristocracy. Political infighting in democratic Athens (where suffrage was only extended to men who had completed military training) led to an unfocused strategic campaign marred by Athenian hubris, ultimately resulting in victory for oligarchic Sparta. Born into a war that would not see conclusion until well into his twenties, Plato began to formulate new political systems that he presumably hoped might make up for the failures of his own city-state.

The more obvious influence on Plato’s thought is the trial of his teacher, Socrates, who was sentenced to death for “charges of impiety and corrupting the youth.”2 Plato reports in his Apology that Socrates is ultimately convicted by a jury vote of 281-220, which we can only assume did not generate any more faith in democracy within the young philosopher. There is also a small detail that is more relevant to our interests here: Plato implies that the comic play The Clouds, in which Socrates is lampooned as a sophist (more on that later), was a critical piece of evidence that shaped the jury’s negative opinion of Socrates. Additionally, Plato mentions that the main cohort taking Socrates to trial included poets.3 Plato’s distrust of poetry and art in general is made explicit throughout his writings, and his feelings on the matter almost certainly hardened here, with the conviction of his mentor and close friend.

Although Socrates died without having written a word, he still lives quite vividly within Plato’s pages. Nearly all of Plato’s works are dialogues, i.e. conversations between a group of people written out like a play, the majority of which feature Socrates as the main character and, importantly, never include Plato himself. This makes it hard to attribute anything said within the dialogues to Plato - are the views the characters express Plato’s, or is there some kind of strange ironic distance between him, them, and us? Are any of the assertions supposed to be taken at face value, or are they actually meant to highlight the ultimate failure of philosophical thought to reach any final conclusion? Some of the arguments posed by the dialogues have pretty clear flaws, flaws so clear Plato must have been aware of them, which suggests his true point is often something unsaid.

There are no easy answers to these questions, and the impossibility of pinning down Plato or Socrates to any one position leaves us unable to talk definitively about the philosophers themselves. Plato’s ultimate contribution to the field of literary theory is therefore not any concrete point, so to speak; instead, literary theory has had to reckon with the questions he poses, questions which are still difficult to resolve today. Does art reflect truth? What is the nature of its creation? What influence does it have over the individual, society, and the state?

For the sake of clarity, and since it’s impossible to attribute any claim specifically to Plato, I’ll be referring to Socrates, Plato’s effective mouthpiece, throughout these summaries. We just have to keep in mind that this is Socrates the character, who may or may not be consistent with the historical Socrates.

Ion

Ion, like most of the dialogues, is named after the person Socrates converses with. Ion is a rhapsode, an itinerant professional performer of epic poetry, who specializes in Homer, and as a matter of fact has just come back from a festival where he won first place in a rhapsode contest. A rhapsode primarily recited poetry for an audience, but importantly they also served as proto-literary critics, as they were expected to explicate the works they recited. Ion can not only recite Homer’s works from memory, a supremely impressive feat, but can also explain what Homer’s works mean: “A rhapsode must come to present the poet’s thought to his audience; and he can’t do that beautifully unless he knows what the poet means.”4 Socrates congratulates Ion for his victory but quickly enters an extended line of pedantic questioning Ion is clearly not prepared for or even interested in. Socrates wants to know if rhapsodes, and by extension poets, do what they do (interpretation and composition respectively) via knowledge or skill, or if, as Socrates later proposes, their feats are due to divine inspiration and creative madness.

Ion claims he is an expert on Homer and only Homer, and that Homer is the best of all poets. What bothers Socrates about these claims is that Ion is saying he knows nothing about other poets while also making a qualitative judgement by saying Homer is the best of all the poets. To be able to do so, argues Socrates, would require a certain kind of knowledge. He makes a comparison to nutrition: if one has knowledge of nutrition, that means one knows what good nutrition is, and therefore can distinguish between two people offering good and bad nutritional advice. If you could not do so, then one wouldn’t have knowledge about nutrition. He then generalizes this logical statement:

So, to sum it up, this is what we’re saying: when a number of people speak on the same subject it’s always the same person who will know how to pick out good speakers and bad speakers. If he doesn’t know how to pick out a bad speaker, he certainly won’t know a good speaker - on the same subject, anyway.”5

Ion agrees, and Socrates proceeds:

SOCRATES: Now you claim that Homer and the other poets (including Hesiod and Archilochus) speak on the same subjects, but not equally well. He’s good, and they’re inferior.

ION: Yes, and it’s true.

SOCRATES: Now if you really do know who’s speaking well, you’ll know that the inferior speakers are speaking worse.

ION: Apparently so.

SOCRATES: You’re superb! So if we say that Ion is equally clever about Homer and the other poets, we’ll make no mistake. Because you agree yourself that the same person will be an adequate judge of all who speak on the same subject, and that almost all the poets do treat the same subjects.

ION: Then how in the world do you explain what I do, Socrates? When someone discusses another poet I pay no attention, and I have no power to contribute anything worthwhile: I simply doze off. But let someone mention Homer and right away I’m wide awake and I’m paying attention and I have plenty to say.

And then the whammy:

SOCRATES: That’s not hard to figure out, my friend. Anyone can tell that you are powerless to speak about Homer on the basis of knowledge or mastery. Because if your ability came by mastery, you would be able to speak about all the other poets as well.”6

He didn’t have to be rude about it, but the point is made: whatever it is that allows Ion to speak so beautifully and authoritatively on Homer, and whatever it was that allowed Homer to write the original verse, cannot be a form of knowledge. If it were, certainly Ion could contribute something of value when discussing other poets. Here we already see some weaknesses in the debate, because whether we like it or not Ion is our representative, and although one wants to shout, “Just say you know something besides Homer!” we cannot. Socrates then introduces the famous metaphor of magnets and iron rings: “…it’s a divine power that moves you, as a ‘Magnetic’ stone moves iron rings.”7 Just as the original magnet “sends” its magnetism through one ring to the next, each serving as a conduit for that attractive and capable force and creating a kind of chain, so too do the gods inspire the poet, who in turn inspires the rhapsode, who in turn inspires the audience, themselves creating a chain of divine feeling. Socrates asserts that this is the true source of poetry:

You know, none of the epic poets, if they’re good, are masters of their subject; they are inspired, possessed, and that is how they utter all those beautiful poems… For a poet is an airy thing, winged and holy, and he is not able to make poetry until he becomes inspired and goes out of his mind and his intellect is no longer in him. As long as a human being has his intellect in his possession he will always lack the power to make poetry or sing prophecy.”8

This idea has a lot of currency even today. Although we, unlike Socrates in this dialogue, acknowledge that writers have some kind of “hard” skill, there’s still this idea that writers are kind of “crazy,” and that some strange alchemical process has to happen for real art to be produced. For us today, living our largely secular lives, this is just a kind of notion, not something anyone necessarily believes in consciously, but Socrates means it quite literally: the poets “are not the ones who speak those verses that are of such high value, for their intellect is not in them: the god himself is the one who speaks, and he gives voice through them to us.”9 The notion of divine inspiration as the catalyst for the artistic process is going to remain popular for a long time moving forward.

Whether poets know anything, or whether poetry conveys anything of “value” may seem fairly unimportant to us today, as we are largely conditioned to view art as “entertainment,” which I would argue is a fairly recent and nauseating development. For Plato, however, the argument had fairly high stakes. Homer’s work, along with those of other poets’, formed essentially the entire curriculum of ancient Athenian schooling, and therefore was used as the basis for learning about the world - there was, after all, very little to go off of. These texts were studied as the definitive authority on all matters of life. Reading the Iliad and Odyssey was supposed to lead to knowledge of what a good life consisted of, what values were important, and so on. When Socrates interrogates Ion about whether he knows anything, he is simultaneously asking the implicit question, Should poetry form the basis of education? It is not a stretch to say Homer effectively invented Greek culture by writing his twin epic poems, so Socrates’ inquiry is attacking not only poetry but the entire foundation of contemporary Athenian life. But the question remains relevant even today - what are we really learning when we read Catcher in the Rye or “Harlem” in the classroom? Do they contain anything we might call knowledge? Is there any reason literature is worthwhile besides the fact we said so? Do the values they espouse have any basis in reality? And who do those values serve?

Importantly, Socrates’ critique is not just addressing Homer and the poets, but Ion and the rhapsodes as well. For Socrates, literary criticism itself is empty of substance, and is only a derivative madness received from the original poets. This cuts two ways; it makes the act of interpretation itself divine (which made a lot of people happy, as we’ll see when we get to Biblical interpretations in the middle ages), or at least artistic in some sense, but also suggests criticism is based on nothing substantive, which is a view still widely held today - what are all these snobby art critics talking about? How are these shitty modern art exhibits still getting rave reviews? And if criticism by nature is not based on knowledge, then on what merits can we evaluate art at all?

The dialogue goes a bit further, with Socrates questioning more specific parts of Ion’s knowledge. Socrates mentions that Homer writes about charioteering, and asks Ion if Ion himself or a charioteer would be better equipped to speak about the passage in question, and Ion says a charioteer. Socrates uses this as further evidence that Ion and Homer don’t know anything. This is a bit of a stretch. The modern comparison would be movies; if you’re an expert in some field, let’s say computer science, and you go to the movies and see a hacking sequence, you will have the requisite knowledge to say that movie is “bad,” i.e., is not accurate. A movie critic would not necessarily be able to make that judgement, according to Socrates. The obvious issue here is that today, whether a movie is good or bad is often independent of the accuracy of its subject matter. James Bond isn’t an accurate depiction of spies, but we might still say Casino Royale is a good movie (it is). The reason Socrates has this standard is, again, because Homer’s texts were used as the basis of education, so a certain level of accuracy was desired if you were trying to educate an entire society using his poetry. Regardless, the important underlying idea here is that Socrates sees art as didactic, with very specific educational and political goals. This is the beginning of a long tradition in literary criticism that we’ll pick up on in the future.

The dialogue ultimately concludes with Ion, exasperated, admitting that yes, I am divine, Socrates. “Then that is how we think of you, Ion, the lovelier way: it’s as someone divine, and not as master of a profession, that you are a singer of Homer’s praises.”10

From Republic

The Republic is Plato’s best known work and covers a lot of ground, including definitions of justice, the ideal state, Plato’s theory of forms, and the nature of poetry. There’s a lot of debate on how seriously we are supposed to take some of the ideas presented here. Is the “utopia” described by Socrates actually Plato’s idea of a utopia, or is the discussion of it supposed to reveal that such a city could never be, or that our attempts at utopian ideals will result in terrible societies? I don’t want to get bogged down too much in this since you could literally write a dissertation on it and different thinkers throughout time have taken different views on the matter, so I’m going to discuss most of it at face value, with some comments accounting for the fact that Plato might not really mean it. Also, as noted previously, these are just excerpts that pertain to literature, so we’re not reading all of the Republic and getting into the nitty-gritty of justice and the ideal society. Then we’d be here all day.

From Book II and III

Socrates, in dialogue with Adeimantus, Plato’s real life brother, is discussing the ideal education of the ideal rulers of an ideal state. This discussion started in Book I with the men trying to define justice and failing. Socrates pivots, and says it would be easier to seek justice in a city rather than in a person’s soul, so he begins to imagine a truly just city. Such a city would naturally (naturally) have to be ruled by philosophers, and they would require a special education. Since this ideal city is ultimately metaphorical, it’s unclear to what extent we are to take Socrates’ pedagogical strategies seriously. Regardless, things get weird pretty fast.

Socrates suggests the education should consist of music (which includes “poetry and stories”) and gymnastic (education for the body). “We shall tell tales and recount fables that will serve to educate them.”11 But wait! Children, being so impressionable, should only hear stories with “the kinds of values we deem desirable for them to have when they become adults.”12 “Then our program of education must begin with censorship.”13 Gasp! Already off to a pretty bad start here in our ideal state. Socrates feels censorship is necessary because certain stories “tell lies,” and that these lies are “malevolent” and will result in the citizens of this utopia growing up to be naughty. He uses the myth of Zeus killing his father, Cronos, as an example. If this story was told in our society, wouldn’t our children then grow up believing acts of revenge against their fathers are not so bad, and perhaps even ought to be emulated, since of course the gods are perfect, and it would be good to follow in their image? Socrates says these stories should only be told “to a chosen few under conditions of total secrecy. And this only after performing a sacrifice not of an ordinary pig but of some huge and usually unprocurable victim. That should help cut down the number of listeners.”14

The level of censorship and historical revision Socrates advocates for is pretty extreme. “If we could get them to believe us, we would tell our future guardians that quarreling is a blasphemy, and we would say that to this day there has never been a quarrel among citizens.”15 Our perfect state is slowly coming to fruition. Socrates targets religion as well: “The proposition that a god, who is good, should cause evil to anyone is something we must strenuously deny.”16 This actually jives pretty well with our Judeo-Christian ideas of divinity (the common objection “If God is real why is there suffering in the world?” hinges on the idea that God is necessarily perfect and good) but doesn’t accord with the countless myths of Zeus turning into various animals and raping whomever he pleased. This is a pretty strong condemnation from Socrates, since so much of the literature in circulation at the time depicted the gods acting very selfishly and going far out of their way in order to satisfy their basest desires. We certainly can’t have the citizenry doing that.

In Book III, Socrates says that the state’s guardians “must learn not to fear death.”17 He even says “we must expand our supervision to those who write and tell stories about these matters, too. We must ask them to speak better of Hades…for what they tell us now is not true, nor is it edifying for those who are going to be warriors.”18 He elaborates and says that boys and men should be schooled “to fear slavery more than death.”19 This last point is explicitly made with the intent to stop men from surrendering in a losing battle and instead fight to the death - clearly literature’s true purpose in our ideal society. He also takes issue with Greek poetry’s frequent depiction of emotional men, who are the absolute worst, and absolutely would not help our military in its mission for world domination. “Then we shall do well to delete the lamentations of famous men. We can attribute them to women - and not to the better sort of women either…We do this so that those we educate to be guardians of the city will disdain such behavior.”20 Toxic masculinity in 330 BCE, who knew. “Nor must our young men be too fond of laughter.”21 In case you thought, hey, maybe this won’t be so bad, Socrates has some special rules. “Only the ruler of the city - and not others - may tell lies.”22 This take has aged pretty well, considering every governing body today takes it to heart.

Socrates renews his attack on poetry, and in particular Homer, from Ion. One of the climactic scenes in the Iliad is when Achilles, having just killed Hector, Troy’s greatest warrior, drags his corpse around in circles behind a chariot, in lieu of doing funeral rites or handing the body back over to the Trojans, as was custom. “That Achilles actually did these things is something we must not believe. We shall reject the charges that he dragged Hector’s body around the tomb of Patroclus and slew living victims on the funeral pyre.”23 For the first time, however, Socrates wonders if our ideal state’s censorship will apply to other art forms: “…should we extend our guidance to those in the other arts and forbid representations of any kind of evil disposition - of what is licentious, illiberal, and graceless - whether in living creatures, in buildings, or in any other product of the arts of man?”24 For Socrates, the “purpose of poetry and music is to cultivate the love of beauty,”25 and thus all these images that depict what we might call “evil,” “lesser,” or “unvirtuous” things have to go. Again, we see Plato’s interpretation of art’s purpose as purely didactic, an idea that will basically never go away.

He also claims that “education in poetry and music is first in importance…Rhythm and harmonies have the greatest influence on the soul; they penetrate into its inmost regions and there hold fast.”26 For Socrates, the link between poetry and politics is obvious; without proper, virtuous cultural products circulating in society, the collective population is prone to succumbing to their vices. While we may disagree with Socrates over precisely what the virtues and vices of our ideal city may be, the larger point that poetry, and by extension art, is the most important variable in influencing the behavior and beliefs of people, is crucial, and foresees a lot of discourse on the effects of cultural products for centuries.

From Book VII and X

Book VII contains the very very famous Allegory of the Cave. In this fairly simple tale, Socrates asks us to imagine a cave in which people are shackled so tightly they cannot move or even turn their heads. They are forced to face a wall while behind them a fire burns and strange beings hold up objects in front of it, casting shadows upon the wall. If their entire lives had been spent like this, wouldn’t they perceive the shadows cast upon the wall to be reality? And if they were to escape, and walk out of the cave, wouldn’t their eyes burn from the light of the sun until they had adjusted? Socrates claims this is actually what our reality is like, and that the journey out of the cave is like our soul’s journey toward Truth. One often neglected aspect of the allegory is Socrates’ description of a person who reenters the cave - wouldn’t such a person, whose eyes had adjusted to the light of the sun in the “real” world outside the cave, have difficulty readjusting to the darkness of the cave when they returned? And when asked by the cave dwellers to interpret the shadows upon the wall, would have nothing to say, other than all that they know is false? The idea being, after one has been exposed to Truth and acquired new knowledge, it’s very difficult to talk to people still in ignorance about that ignorance, and that wise people can often seem very silly. Neat!

We now have to pause to discuss Plato’s theory of Forms, which is not explicitly laid out in these excerpts but is alluded to throughout the Allegory of the Cave and Book X. The gist is that our reality is populated by beings and things that are copies of Forms, which make up actual reality - there are billions (trillions?) of trees in the world, but they all take the capital F Form of a tree. Every possible thing you can think of has a Form, and not just “real” things but abstract ones as well, like justice, or geometric shapes. You can’t draw a perfect circle, but you certainly have the idea of one in mind when you try to, and that’s a kind of reality, too. Importantly, Plato doesn’t see Forms as simply abstract mental artifacts, but as actual things existing in the realm of Forms, which is “accessible not through the senses…but only through rigorous philosophic discussion and thought, based on mathematical reasoning.”27 The world of appearances that we see and interact with is simply the shadow of the world of Forms, just as the shadows in the cave are cast by actual things held above the fire.

Socrates furthers this theory in Book X. He uses the example of a bed; basically, there are many beds, but each of them refer to this “parent idea” of a bed which is the Form. He notes that both carpenters and painters can “make” beds. Glaucon, his interlocutor at this point, says, well, a painter doesn’t really make beds, they just recreate the appearance of beds. Socrates agrees, but argues that the carpenter doesn’t actually make beds either - he is simply making a “facsimile” of a bed, a copy of the form, and the painter makes a facsimile of a facsimile. “No wonder, then, that the one who makes beds also offers only a dim reflection of the truth.”28 Indeed.

Unsurprisingly, Socrates pivots immediately to poetry. “Some say the tragic poets know all the arts, all things human, all things pertaining to virtue and vice, all things divine. They claim that the good poet writing good poetry must know what he is writing about; otherwise he would not be able to be a poet.”29 A lot of absurd argumentation follows. Socrates says that if Homer truly knew so much about war and military matters, he would have been a general, not a poet. Additionally, if Homer had really known so much, wouldn’t people have crowded around him, willing to pay to learn at his feet? Then why did he become an itinerant poet? In other words, the market would have naturally found and rewarded Homer for his expertise, and never cursed him to a life of composing verse. Socrates thus condemns him to simply aping the world of appearances: “…the entire tribe of poets - beginning with Homer - are mere imitators of virtue and imitators as well of the other things they write about.”30

This idea of imitation, or mimesis, is critical. For Socrates, artists are at a “third remove from nature.” They produce images, verbal or otherwise, which are meant to depict reality, which is itself a copy of the realm of the Forms. When Homer paints some image with his words, reality is invoked, but it is a sham reality. Not only is this imagined reality not useful, it is actively unhelpful, in that it moves us away from capital T Truth and “goodness,” which is the ultimate goal of life according to Socrates. This is the crux of the overarching argument Plato wages against poetry throughout all the excerpts here, that it reflects nothing but an already false reflection, and it’s difficult to overstate how influential this specific criticism will be in the future. Images and language used in poetic capacities mislead us, they inspire misguided behaviors and trick us into thinking reality is like its depiction, when in fact it is something different entirely.

“Everything finds expression in three arts,” continues Socrates: “the art that uses, the art that creates, and the art that imitates.”31 He then privileges the art that uses, and argues that people who use things possess the most knowledge about those things, more so than the person who makes or imitates them. Ok, this isn’t the craziest argument, but it’s certainly not a given, and the easy counter example today is computers, which I know exceedingly little about, despite using them. I think we can agree that the content of knowledge is different between users and makers, although the industrial revolution and the division of factory labor in particular has effectively vaporized knowledge about making, so from our historical moment it may be nigh impossible to consider this argument on its own terms. Socrates, never one to dawdle, does not pause to consider us here in 2022 and leaps forward in his line of thought: “Then neither knowledge nor opinion can help the imitator to arrive at valid judgements about his own imitations…and never will he understand why something is bad or good. And what he will imitate is all too evident: whatever pleases the ignorant masses.”32

Is it true that neither knowledge nor opinion can help us judge “imitations?” It’s a difficult question that is certainly still considered today when discussing art. The modern cop-out is “Art is subjective,” which may well be true but doesn’t resolve any of the tension behind this assertion - and of course Socrates is saying that even opinion won’t help us in our aesthetic judgements! He doesn’t flesh this thought out much, so it’s hard to understand his precise thinking, but it signals some irresolvable contradictions within literary criticism. As for pleasing the ignorant masses, market forces have unquestionably altered the trajectory of popular culture and artistic outputs over the centuries, and although some art has resisted the allure of fame and notoriety, we cannot dismiss his point entirely.

Socrates then mounts his final push against poetry. He privileges (again somewhat arbitrarily) reason over emotion, and says that poetry appeals to the latter over the former, and therefore “cannot be our companions or friends for any good or healthy purpose.”33 He then highlights two contradictory impulses using the example of grief; if a “good man” is grieving the death of a loved one, he will “make greater efforts to fight back and endure the pain” when he is with people as opposed to when he is alone.34 Socrates and Glaucon are working under the assumption that grief is bad, that we need to move on from our suffering and look to the future. But when we hear the lamentations of “good men” in Homer’s verse, for example, we have almost the opposite reaction: “We are held captive by the imitation; we suffer with the hero, and whoever can most powerfully evoke this mood in us we call the best poet.”35

Why do we praise a poet for making us feel grief, or any other emotion, when we wish to hide our own grief from each other? Socrates refers to this as “[t]he poet’s power to corrupt even the best men.”36 We pride ourselves on keeping it together, yet are moved when poets depict great emotion. Today we might make much of this discrepancy and credit it to toxic masculinity or societal pressures, but even accounting for that there is no doubt that literature and art in general depict a range of emotions and behaviors that are often considered taboo. The idea of art as a kind of escape valve for “repressed” feelings will come up again throughout the anthology. Socrates lingers:

Sex, anger, and all the desires, as well as all the pleasures and pains that make their presence felt in whatever we do - on all these poetry has the same effect. It makes them grow great instead of drying them up. It establishes them as our governors when instead they should be the ones governed if we are to become men who are better and happier instead of worse and more miserable.37

So we’re still trying to work out the role poetry should play in the ideal society. Poetry threatens to destabilize the rational self that is necessary for maintaining our social and political order. Another interesting point Socrates brings up is that since emotions are easier to imitate than reason (e.g., it is easier to outwardly express sorrow than it is to outwardly express intelligence), it will always be the latter and not the former that makes its way into poetry, and thus it will always in some way be corruptive.

Socrates closes by mentioning the “old quarrel between philosophy and poetry,” and that we will “surely be the gainers if the case can be made that poetry is a source of goodness as well as pleasure.”38 If only!

From Phaedrus

This is the last and simplest dialogue included in the anthology. It opens with Socrates relaying an Egyptian myth, which the book says is a “Platonic invention,” in which Theuth, also known as Thoth, the Egyptian equivalent of Hermes, comes to Amon, king of Thebes, bearing new “branches of expertise.” One of them is writing, as in the invention of writing, which Theuth offers as a “potion for memory and intelligence.” Amon disagrees: “Trust in writing will make them remember things by relying on marks made by others, from outside themselves, not on their own inner resources, and so writing will make the things they have learnt disappear from their minds. Your invention is a potion for jogging the memory, not for remembering.”39 Well, that’s basically remembering, but whatever. Socrates essentially agrees with Amon here, and criticizes writing for not being able to speak for itself (???):

…if you want an explanation of any of the things [written words] are saying and you ask them about it, they just go on and on for ever giving the same single piece of information. Once any account has been written down, you find it all over the place, hobnobbing with completely inappropriate people no less than with those who understand it, and completely failing to know who it should and shouldn’t talk to.40

This is funny. Socrates then rails against speechwriters, accusing them of also knowing nothing since they…write things down. He says speeches (by which he specifically means reading written speeches out loud) are terrible, because they indicate the speaker has no knowledge, since if they did they could speak off the cuff, from words “written in their soul.”

Although the argument is simple, the trouble Plato gets himself into here is his usage of the myth. The bulk of Plato’s work and his entire theory of Forms is an attack on “images,” yet with the Allegory of the Cave, the imagined city, and now this fake myth, he has used multiple images for educational purposes. If we believe his assertion that images take us further from Truth, with what weight can we accept his arguments here and throughout the dialogues? Not to mention that the dialogues themselves are “images,” and obviously they’re written down! Plato is not dumb, and he must have been aware these contradictions. This strange disconnect between the form of Plato’s arguments and their content raises only more irresolvable questions, leading us further into the mystery surrounding the ancient philosopher and his arch nemesis, poetry itself.

Afterthought

This is obviously super long, but it’s still what I would consider a quick-and-dirty runthrough of Plato’s work here in the anthology. The texts are really quite dense, though easy to read, and I have done a great disservice to him by skimming over some of the finer points of his thought. I have undoubtedly missed some of the nuances of his word choice, including “virtue,” “value,” etc. Nothing can replace reading the texts yourself, but you’re busy, I get it. Next time we’ll look at some other Greek writers who tussle with Plato’s arguments, and some of the ideas here will get fleshed out, including rhetoric, the value of poetry, and content vs. form. I think it will also be much shorter; Plato is second only to Foucault in page count within the tome. In the meantime, feel free to comment on what I got wrong or left unclear.

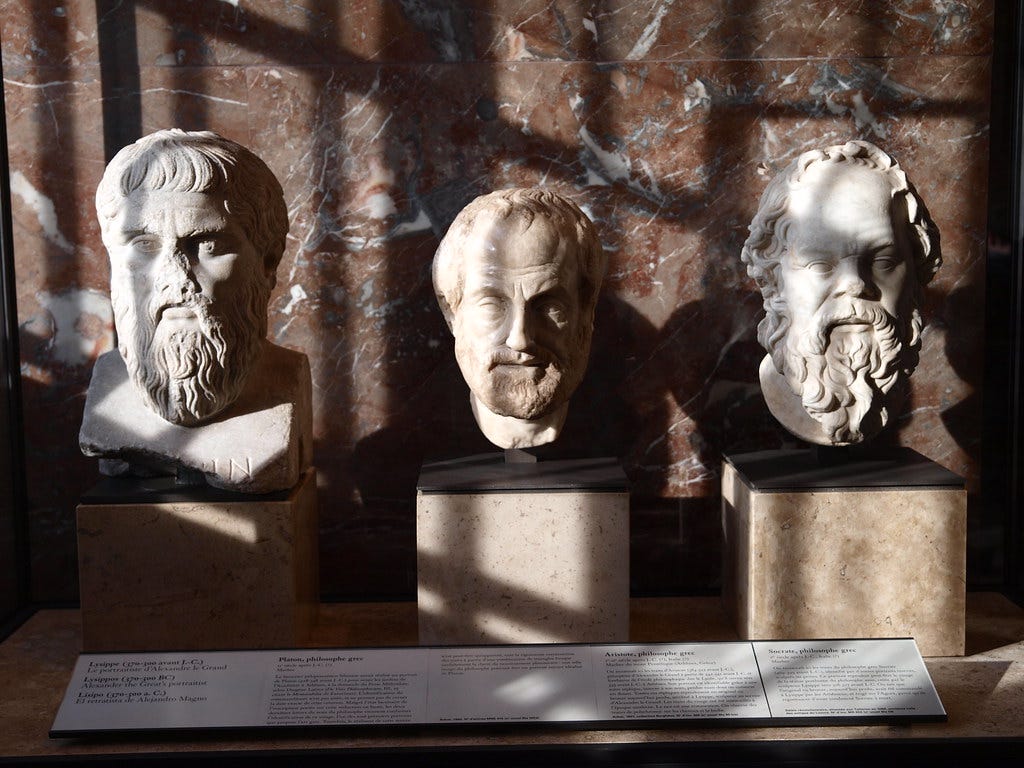

"plato, aristoteles, socrates" by mararie is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Plato,” in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, ed. Vincent B. Leitch (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), 43.

“Plato,” 43.

Griswold, Charles L., "Plato on Rhetoric and Poetry", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2020/entries/plato-rhetoric/.

Plato, Ion, in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, ed. Vincent B. Leitch (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), 47.

Plato, Ion, 48.

Plato, Ion, 49.

Plato, Ion, 50

Plato, Ion, 51.

Plato, Ion, 51.

Plato, Ion, 58.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, ed. Vincent B. Leitch (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), 58.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, 59.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, 59.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, 60.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, 60.

Plato, The Republic, Book II, 60.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 65.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 66.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 67.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 67.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 68.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 69.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 71.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 73.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 74.

Plato, The Republic, Book III, 73.

“Plato,” 45.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 79.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 81.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 83.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 83.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 84.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 85.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 86.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 87.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 87.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 88.

Plato, The Republic, Book X, 89.

Plato, Phaedrus, 90.

Plato, Phaedrus, 91.